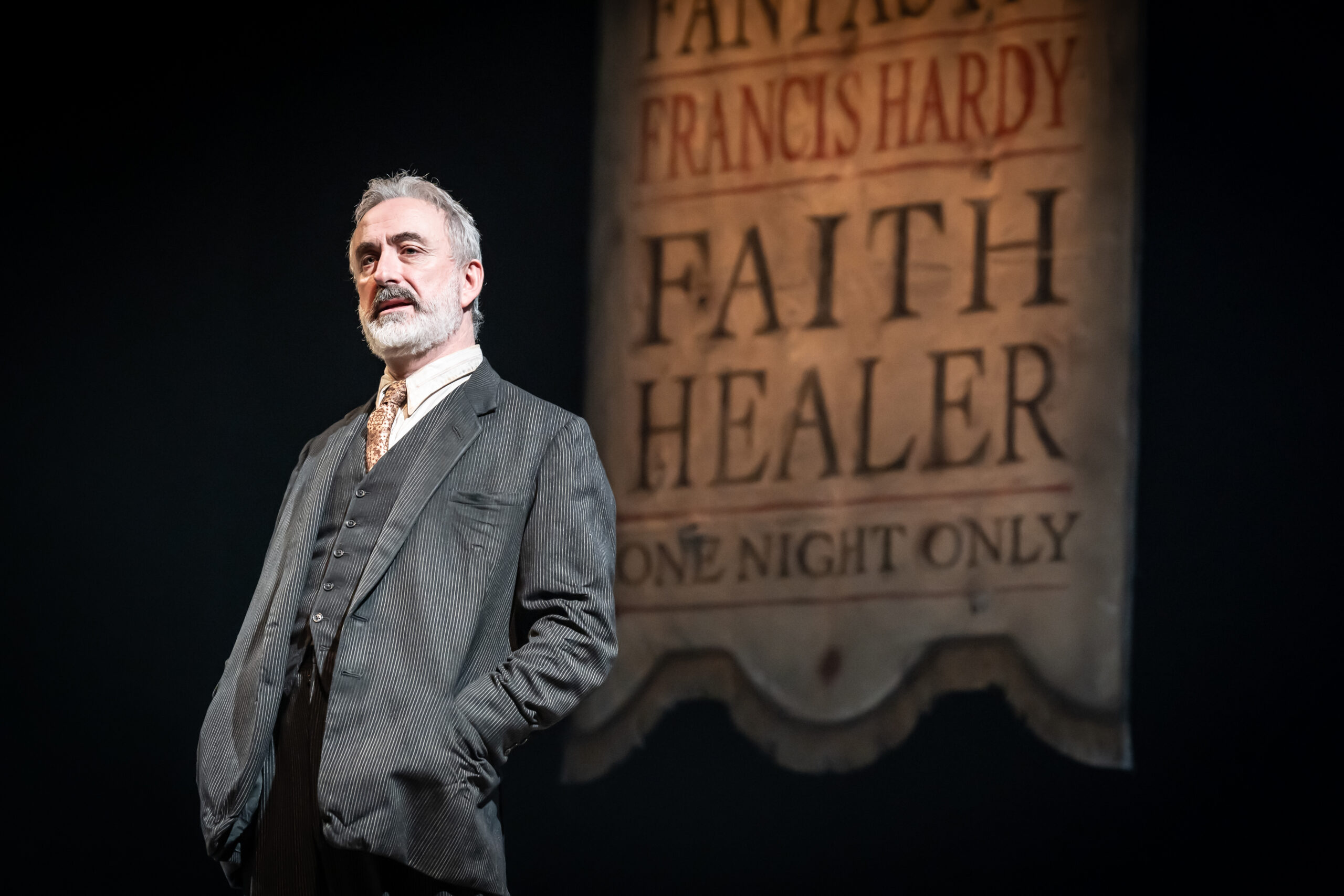

The stage is dimly lit and sparsely decorated – a few long-empty chairs, a tattered advertising banner, dark wooden floorboards that make for echoing footsteps. Here, the audience is transported into the enigmatic world of Brian Friel’s Faith Healer. A mesmerising revival of the 1979 production, Faith Healer delves deep into themes of belief and deception, recollection and impression, love and worship.

The narrative unfolds through a series of monologues delivered by three characters: Frank Hardy, the faith healer; his wife Grace; and his manager Teddy. Each character offers a new perspective on the same series of events, allowing audiences to piece together a fragmented story and discover truths hidden beneath the surface. As the story unfolds, Friel’s monologues weave together masterfully – sometimes overlapping, often missing each other completely.

At the heart of the production lies the character Frank Hardy, presented with haunting intensity by Declan Conlon. As the story is revealed, Frank becomes a figure of both fascination and ambiguity, his gifts as a faith healer juxtaposed with shadows of doubt and stories of drunken ill treatment towards his partner. Faith Healer prompts the audience to explore multiple avenues of Frank’s psyche – grappling with questions of faith, redemption, and the nature of miracles.

In dramatic contrast, Hardy’s wife Grace is portrayed with raw vulnerability by Justine Mitchell. As Grace’s story develops, the audience sees her unwavering, sometimes blind, devotion to Frank. Mitchell presents the character skilfully, discussing trauma such as enduring a stillborn birth at the side of the road, or numerous counts of emotional abuse from Frank with vehement emotion.

In the second act, Hardy’s Manager Teddy serves as comic relief, with equal parts charm and cynicism. Faith Healer reveals Teddy as the voice of reason – his story often falling somewhere between that of Frank and Grace’s opposing versions.

Owing to its masterful performances, Brian Friel’s captivating script and pitch-perfect direction from Rachel O’Riordan, this production captivates from the opening scene to the final curtain. At its core, Faith Healer is a meditation on human needs, wants and desires – it invites audiences to tread the fragile line that separates reality from illusion.

Featured Image: Declan Conlon in Faith Healer (c) Marc Brenner

Faith Healer is written by Brian Friel, directed by Rachel O’Riordan, set and costume design by Colin Richmond. lighting design by Paul Keogan, composition and sound design by Anna Clock, casting by Sophie Parrott CDG

Faith Healer is a Lyric Hammersmith Theatre production. For more information on their current and upcoming visit Homepage – Lyric Hammersmith

Review by Amy Melling:

Amy is a Curator and Creative Producer whose practice is centred around community-led arts projects. Her current research is focused on curatorial methods for exhibiting artworks outside. Amy has a keen interest in the arts and recently completed an MA in Curating and Collections at Chelsea College of Arts, UAL.

Read Amy’s latest Review: When Forms Come Alive “a rapturous exploration of sculpture” – Hayward Gallery, until 6 May – Abundant Art