Fourty years have passed since the release of the 30-minute television series “Ways of Seeing” created by writer John Berger and adapted to a book of the same name in 1972. In it, we read: “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” But what does it mean to be looked at? The Dulwich Picture Gallery answers the question with an exhibition dedicated to the enigmatic motif of the ‘woman in the window’. It makes us re-evaluate the very act of looking.

Inspired by Rembrandt’s 1645 painting ‘Girl at a Window’, the exhibition brings together over 40 works by artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, David Hockney, Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman, and Wolfgang Tillmans and reveals how artists have long used the age-old motif of the ‘woman in the window’ to elicit a particular kind of response ranging from empathy to voyeurism. Featuring a range of media including sculpture, painting, print, photography, film, and installation this show makes us re-consider issues of gender and visibility.

‘Reframed: The Woman in the Window’, is filled with revelations. It convincingly denies the widely accepted claim that Dutch artists of the seventeenth century had a monopoly on the woman and window concept. The oldest work here dates right back to 900BC when a Phoenician artist carved the face of a temple prostitute on a piece of ivory. The ancient ivory and pottery on display showed women peering through the open-air windows with such abrupt and defiant frontality as to make the viewer reel back. These works reveal the early history of the motif and its use in representations of power, seduction, spirituality and the afterlife suggesting a view of a spectacle beyond. Here the window seems to act as a door between secular and sacred worlds, ironically referred to as a proxy for the female anatomy.

Warning against the ‘lust of the eyes’ that could lead to sinful thought, dominated Medieval and Early Renaissance depictions of people looking out of a window. Exceptions were made for representations of the Virgin and Child. An example dating to 15th century recalls her role as Queen of Heaven. The Virgin is staged to be adored while standing at the ‘window to heaven’, yet she cautiously avoids gazing at our eyes looking down at her infant. Her presence expresses her own attitude toward herself and defines what can and cannot be done to her. This idea encouraged fifteenth-century artists to take up the motif as an innovative way of painting female portraits.

For centuries ‘the woman in the window’ represented a female type, a nameless and idealised woman, often reduced to a head or a bust. In defining the ideal nude, Dürer believed that this ought to be constructed by taking the face of one body, the breasts of another, the legs of a third, the shoulders of a fourth, the hands of a fifth – and so on. Similarly, the abstracted or fragmented representations of a woman framed by a window suggest that the female figure is irrelevant and interchangeable, emphasizing the void concealed in her presence. Turning away from the viewer, lost in indecipherable thought Sickert’s woman at the window turns herself into an object, and most importantly an object of vision: a sight. Only the personal and often intimate relationships between artists and their models and muses, witnessed in the works of Picasso and Wolfgang Tillmans, restore a sense of particularity and individuality to those faces flattened by the frame.

A window is essentially a frame within a frame that might act as a stage as in the case of the woman on the balcony, or as a domestic prison, echoed by all the caged birds in many of the paintings presented in the show. But what it emphasises, almost inevitably, is the loneliness of the figures. Often confined within domestic interiors, occupied in an activity traditionally described as ‘women’s work’ such as sewing or cooking, a woman longingly looks out of the window as in Isabel Codrington’s The Kitchen (1927).

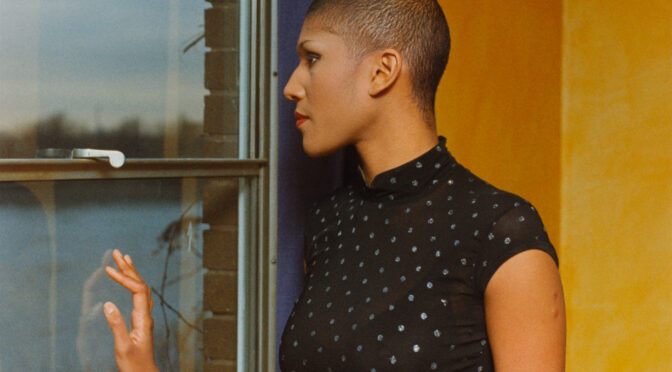

A woman is looking out posing for us, or we are spying on her; we catch her unaware, or the artist holds her in his gaze. She has the world before her, a world she can see but never reach. A key aim of the exhibition is to turn the focus towards women artists who have adopted the concept of the window as a site of communication, connection and inspiration. The last section explores the works of six female artists who have taken ownership of the motif, in some cases using their own body and image to explore the construction of identity.

Men frame women; women reframe themselves with intuition and courage. The show is enthralling, stimulating and intelligent and offers a lesson about both art and life, and the experience of seeing and being seen.

This exhibition is on until 4 September 2022. For more info or to book – dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/2022/may/reframed-the-woman-in-the-window/

Gallery Opening Hours: Tuesday–Sunday, 10 am–5 pm. Closed Mondays except for Bank Holidays.

Reviewed by Rachele Nizi- After completing her MA in Reception of the Classical World at UCL, Rachele joined Abundant Art as a creative writer. Her British and Italian origins have inspired her to want to study Art History and European Literature, with an interest in the afterlife of antiquity in the Western tradition.