Each year the RA Schools offer 15 early-career artists the opportunity to study on its full-time, no-fee, three-year programme. The course, as old as the Academy itself, was founded in 1769 and boasts a plethora of art-world giants in its alumni – JMW Turner, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Michael Armitage and Rebecca Ackroyd, to name but a few.

This year, however, is a little different. The graduating artists have undertaken the programme plus an additional year (2020/21) – allowing them to make up for time lost due to COVID-19. However, this lack of studio time doesn’t seem to have constrained their work as the exhibition sees a whole range of mediums including performance, photography, installation, painting and moving images.

The exhibition exists in the in-between spaces; long corridors leading to dark installations, boiler rooms filled with concrete sculptures, and empty pigeon holes used to hang canvases. Here, the graduates have reconsidered space. They are experimental, playful, and sometimes excessively conceptual – perhaps the only logical outcome of studying through two years of lockdowns?

In one of the first rooms, Luke Samuel’s minimalist paintings stretch the length of the space – they are solid but delicate. The block tones against the whitewashed wall anchor the viewer’s eye to them immediately. Conversely, Kobby Adi’s The removal of all visible and obscured plaster casts, with the promise of being returned, 2022, also catches your eye. Or perhaps that should be, doesn’t catch your eye, as the work is about the absence of these objects – the residual traces still on the wall, showing their outlines. These works are intriguing, they leave you wanting to know more.

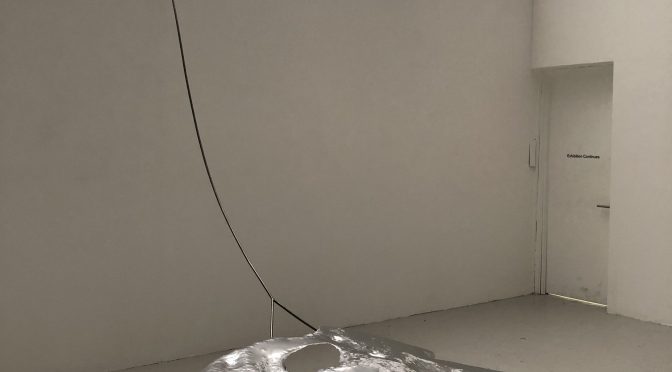

However, a little further on, Rebecca K. Halliwell-Sutton’s multi-media practice stops you in your tracks. Through ions and stratus i, ii, & iii, 2022 sees three aluminum sculptures projected from the walls on curved steel rods. The large 3D works seem weightless, almost like stingrays floating in water. In contrast, on the other side of the space is a small room with a padded bench containing the work Infinite Loop, 2022. Inside, a speaker plays a poem recited in a women’s soft northern accent – it is calming, like a long phone call with a relative. Halliwell-Sutton’s work often explores intergenerational connection through time, bodies and place. Here, the works are powerful, emotive, subtle.

The RA Schools show is showing in the studios of the Royal Academy every Tues – Sun, 10am – 6pm, until 3 July 2022. It is free with no booking required.

Photo of Artist Rebecca K Halliwell Sutton’s piece by Amy Melling (see biog below)

For more info: www.royalacademy.org.uk

Reviewed by Amy Melling – Amy is a Curator and Creative Producer whose practice is centred around community-led arts projects. Her current research is focused on curatorial methods for exhibiting artworks outside. Amy has a keen interest in the arts and recently completed an MA in Curating and Collections at Chelsea College of Arts, UAL.